KYN: Asset Turnover

In this edition of KYN: Know Your Numbers™…

The Asset Turnover Ratio is one of my favorite metrics, especially when working with farm businesses. Despite what one may infer by the name, this ratio is not a promotion of turning over assets any faster than they already are. Quick turnover of assets is a major contributor to profitability challenges and cash flow challenges in the farm space.

In brief, the Asset Turnover Ratio is a measurement of how efficiently a business uses its assets to generate revenue. The calculation indicates how many dollars in revenue are generated by each dollar invested in assets. Higher is better.

The classic (textbook) version of the calculation is “Total Revenue” divided by “Average Total Assets.” So if your business generates $2.5million in revenue with $1million in average total assets, then your Asset Turnover Ration (ATR) is 2.5:1.0 (or for simplicity, just 2.5).

Here’s what I don’t like about Asset Turnover Ratio:

- It uses “average” total assets. I have never liked using average; I feel “average” is way to make substandard performance look acceptable.

But more to this case specifically, how do we “average” the total assets in your business? If you just take the total at the beginning and the end of the year and average those two figures, you will get an “average,” but how accurate is it? Should we be measuring assets each month and average 12 measurements? What about assets that are acquired then disposed of very quickly between measurement strike dates? I’m not a fan of average. - There is no clarity between which value to use when measuring assets (I.E. market value or book value)

- The calculation does not, by definition, include leased assets (leasing has become quite popular.)

- To be truly meaningful we must recognize that each industry has different Asset Turnover Ratios that are considered acceptable; sometimes the differences exist even within a similar space. Consider retailing: online retailers would have significantly lower investment in assets than retailers with brick & mortar store fronts. Online retailers would have significantly stronger ATR accordingly.

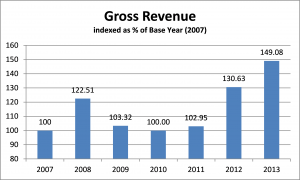

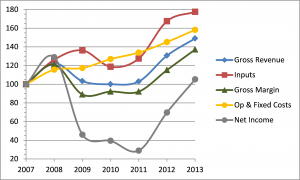

Once we clarify how we will approach the Asset Turnover Ratio, and maintain consistency in that approach so as to accurately trend your ATR metric over time, the ATR becomes a strong indicator of your business’ efficiency.

- Determine how you will value your assets:

– when will you measure the asset values (frequency, date(s), etc.)

– eliminate confusion and ambiguity…do two calculations, 1 with market value of assets, and 1 with book value

– do not exclude assets under a capital lease, it will provide a false positive. Assets under a true “operating lease” can be excluded. - Understand how your ATR applies to your industry. If there is a deviation in your results versus industry, is it stronger or weaker; what is causing it?

What I like about Asset Turnover Ratio:

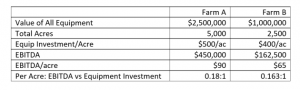

- it creates a stark illustration of how well a business utilizes its assets (which is a MAJOR draw on capital)

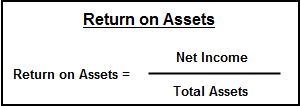

- it is a key driver of ROA (Return on Assets – a KEY profitability ratio) and OPM (Operating Profit Margin – a KEY efficiency ratio) both of which need to be monitored closely

- it shows the DOWNSIDE of asset accumulation (which, in the farm space, is a difficult conversation.)

Trending performed over many years by advisors with experience durations that are multiples of my own suggest that grain farms and cow/calf operations have ATR in the range of 0.33 to 0.17. Feedlots and dairies typically range from 1.0 to 0.5. User beware: these measurements are using the classical textbook definition.

Plan for Prosperity

As with any financial ratio, evaluating only one ratio does not tell the whole story. As with any financial analysis, how the numbers are quantified will have a profound effect on the results. This is not permission to ignore these important financial indicators, but more so a call to action to understand how each one affects your business so that you can make the informed decisions that will lead to profitable growth.

Not understanding the factors that affect your business is no excuse to ignore them…especially when they are within your control.