Push and Pull

Push and pull.

Passive aggressive.

Proactive or reactive?

Okay, passive aggressive doesn’t REALLY apply…or does it?

A recent conversation with a banker had him using terms & phrases such as:

- they have no idea what they owe, to whom, or what their payments are;

- they leave out information in what they send to us;

- after a year of battling over their lack of cash management, the bank is viewing their risk profile as ‘high.’

- the promised to put together a plan months ago, but it seems there was always ‘something more important’ to do. Now that the bank is downgrading them, they’re in a hurry to get the plan in place.

The borrowers that this banker was speaking of have consistently displayed a behavior that is reactive. They:

- only provide info to their lender when threatened;

- do not follow the terms set out in their borrowing agreement;

- only got serious about making a plan when the bank indicated that their credit risk profile was being downgraded.

Situations like this are, sadly, not uncommon. All too often, financial professionals see impending challenges and offer advice that is pertinent based on their experience. Whether the advice is heeded or ignored is out of our control.

What can be done? At risk of sounding like a broken record…

- Preserve cash by building strong working capital;

- Do not acquire capital assets with working capital…borrowing is still incredibly cheap!

- Drive down overhead costs so you can produce at the lowest Unit Cost of Production.

The challenge, of course, is now during a period of low commodity prices, how does one go about preserving cash to build working capital. A pessimist might say “that ship has sailed” with the end of the commodity boom. Notwithstanding any significant production issues somewhere on the globe, this may be true. And to bring it back around to the open of this commentary, proactive or reactive, it seems that by and large farms are reacting to the profitability challenges and positive cash flow challenges of the day. Proactive would have acknowledged that the good times were cyclical and would not last forever…

Plan for Prosperity

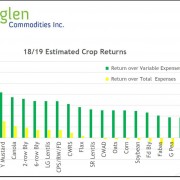

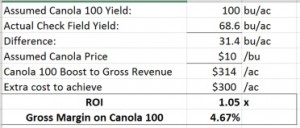

PUSH yields. In commodity production you need the bushels, but focus on optimum yield for profitability, not maximum yield for coffeeshop bragging rights!

PULL efficiency. You need to do more with less in low margin environments.

PUSH costs down. The lowest Unit Cost of Production (UnitCOP) wins. Period.

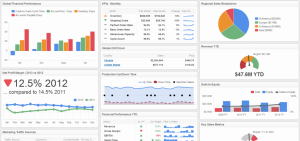

PULL management effectiveness to new heights. During times of questionable profitability, it is management that will rise to the top.