KYN: Debt Structure

In this edition of KYN: Know Your Numbers™, we build on the previous topic of Debt Ratio by looking deeper at Debt Structure.

Debt Structure refers to the ratio of current/short term debt to long term debt in your business. This metric provides insight into how you are financing your business’ needs.

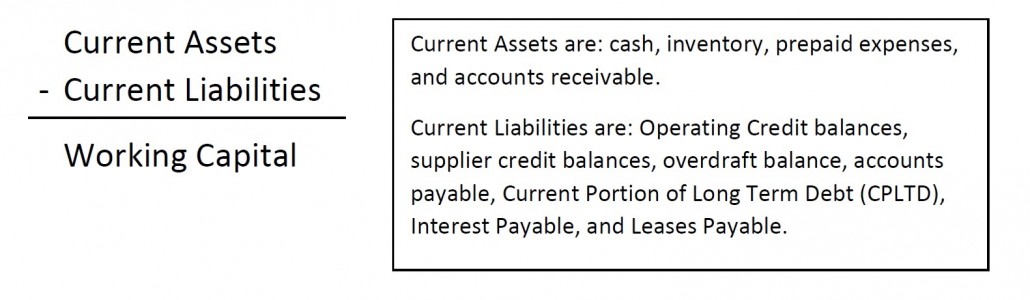

Those who know me know that I am consistent in my belief that short term assets should secure short term debt and long term assets should secure long term debt. This is because short term debt (think about your current liabilities) is expected to be paid off with current assets (like cash) whereas long term debt would be paid out with fixed assets (if a lump sum is required versus retiring the debt over time with regular payments.) That premise is Financial Management 101, and while not a hard and fast rule, it is sound guidance.

More to the Debt Structure conversation, we calculate this ratio by dividing Current Liabilities (all payments and payables due in the next 12 months) by Total Liabilities; same for Long Term Liabilities (total debt not yet due within the next 12 months.) Here is an example:

| Current Liabilities | Long Term Liabilities | |||

|

Accounts Payable |

$1,350,000 | Long Term Debt (LTD) | $3,100,000 | |

|

Overdraft |

$687,000 |

Shareholder Loan |

$300,000 |

|

|

Taxes Payable |

$27,350 |

|||

|

Current Portion LTD |

$487,000 |

|||

| TOTAL | $2,551,350 | TOTAL |

$3,400,000 |

In this example, there are total liabilities of $5,951,350 (calculated as $2,551,350 in Current Liabilities + $3,400,000 in Long Term Liabilities.) The debt structure is 42.8% short term and 57.2% long term. While this is good to know, the next question is “So what?”

On its own, the debt structure ratio does not carry much weight. The value is found in trending the debt structure ratio. For example, if your short term debt trend is increasing it may be an indication of liquidity challenges in your business.

Ideally, calculating your Debt Structure Ratio will cause you to ask more questions and seek more clarity, such as:

- What types of debt make up my short term liabilities? What are these debts for?

- Are my short term liabilities trending up, down, or remaining fairly steady? Why?

- What is the right ratio of Debt Structure for my business/industry?

With economic indicators preparing us for more volatility than years past, and with interest rate increases on the horizon, it is a good idea to have abundant clarity on your overall debt situation. Understanding your Debt Structure, including how your Debt Structure will affect your business under different economic situations, creates an opportunity to “get your house in order,” so to speak, before things start happening.

Plan for Prosperity

The winds of change are blowing. Are you simply going to lower your sail and wait it out, hoping to survive whatever comes? Or are you preparing to chart new courses so that whatever winds you get you are still able to make progress and move forward?