KYN: Profit Margin

“It’s not what you make, it’s what you keep!”

Prophetic words that apply to every business and simplifies the importance of profit.

Profit Margin is calculated as “Net Profit” divided by “Gross Revenue.” Essentially this calculation tells you how much of every dollar earned in gross revenue is actually profit. The smaller the profit margin, the less you keep.

It goes back over 10 years now to when I was a bank branch manager in a rural community. A client was trying to purchase a lake cottage and was upset with us that we weren’t clamoring to provide them with a mortgage. They worked very hard in their business that provided a service to the oilfield, and had expanded it several times by adding more trucks and employees. In one of their rants on me for not giving them what they wanted (it was more like “demanded” at this juncture) one of the partners (a married couple) said, “What does it take? We made a million dollars last year!” True, their top line revenue was exceeding $1,000,000 in the previous fiscal year; however, their net income – the profit – was just over $15,000. Even adding depreciation and interest back into the calculation (to arrive at EBITDA) there was no way they could service the mortgage they were requesting. Their profit margin was (in a simplified example) 0.015%, which meant that for every $1.00 in revenue they generated, they were retaining $0.015 in profits (1.5 cents profit for every dollar in revenue…hardly sustainable in a cyclical industry.)

What I Don’t Like About Profit Margin

- There are many variations on the calculation:

- gross profit margin

- operating margin

- pretax profit margin

- net margin…just to name a few. Each of these is measured slightly differently and has different meaning in different circumstances. If there isn’t sufficient care in assuring accurate nomenclature, things can get confusing.

2. The calculation, on face value, includes the non-cash depreciation expense (a tax figure) that often does not accurately portray the true market depreciation of an asset.

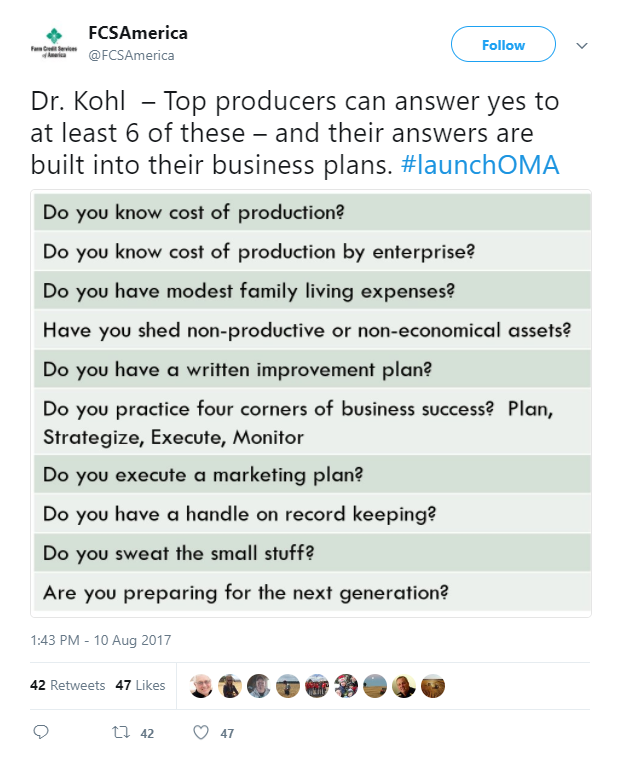

What I Do Like About Profit Margin

When calculated consistently over time, the trend will open up investigation and discussion on variances year over year (YoY) so that corrections can be made if necessary. I also like that it can be an internal benchmark, your own personal KPI (Key Performance Indicator) to which you could measure actual profit margin results against an ideal profit margin target that would fuel your business goals and growth aspirations.

Plan for Prosperity

What is a sufficient profit margin in your business? It is often relative to the industry in which you operate. If you have no idea, a good person to ask is your banker.

After spending virtually all of my professional career working on the financial and business aspects of agricultural production, I can confidently say that western Canadian grain farms need to target a 20% profit margin to sustain their businesses through the volatile cycles that affect the industry. “Target” because some years will blow right by 20%, other years will be low single digits (or negative numbers.) This truly is one space where bigger IS better!

Where has your profit margin measured out over the last 3-5 years? Which way is it trending? Why? If you don’t know the answers, or haven’t asked the questions, there is no time like right now to dig in.