Gross Margin or Operating & Fixed Costs – What Comes First?

The question may seem redundant or nonsensical, 6 of one and a half-dozen of the other…

Do you build your crop plan in an effort to generate sufficient gross margin to cover operating and fixed expenses, or do you budget your operating and fixed expenses to fit within your typical gross margin?

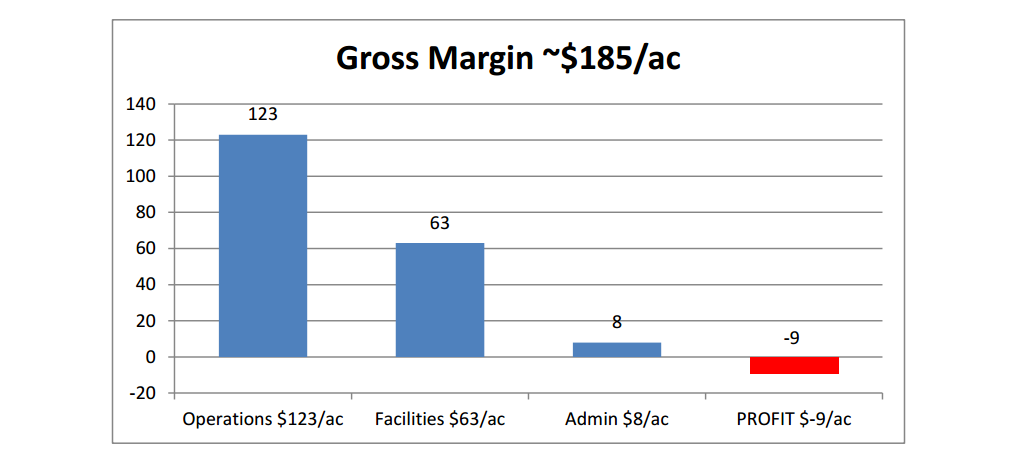

For most high cost operations I speak with, they know their costs are high and then find themselves working hard to generate adequate gross margin to cover their costs and , hopefully, leave a profit at the end.

The challenge that many high cost operators are facing is the run up of their expenses during the recent string of bullish years (land, buildings, equipment, pickups, etc.) and are now trying to manage those residual expenses during a period of tighter margins. They are focusing heavily on one of two areas:

- Seek out every opportunity possible to increase yields and to expose marketing opportunities, or

- Cut expenses to a level more in line with their farm’s historical gross margins.

It seems that the most common strategy that would fall under Point 1 above is to bring lentils into the crop rotation for 2016. The high prices are just too tantalizing to bear for most high cost producers. We will see lentils being grown in non-lentil growing areas in an effort to boost gross margin. I spoke with a young seed grower this month who told me he received a call this winter from north-east of Prince Albert looking for lentil seed. Good luck with that.

I learned of another operation, in an area that is typical for lentil failures, that dabbled in lentils in 2015. While this region can typically produce 30-50 bushel pea yields, this farm enjoyed a solid 5 bu/ac lentil yield. What is the opportunity cost of using land for a 5 bu lentil crop that could have produced a 30 bu, or even 50 bu, pea crop? Chasing rainbows? I’d say so.

A number of my clients are focusing on Point 2 above, and have been quite successful in reducing the one cost that is most controllable, yet has gotten quite high over the last few years: they are selling equipment to reduce their overall equipment cost. Whether it be liquidating the extravagant tillage tool that is only needed once in a while, moving out that sprayer that is too big for the farm size, or not acquiring that “nice to have” tractor, these farms are working to bring, and keep, their costs more in line with their expected gross margin.

Moe Russell has been quoted in these articles before, and he is on record saying, “Over the long term, the price of agricultural commodities will level out at the cost of production of the highest cost producer.” Essentially, if you’re a “highest cost producer,” over the long term you’re looking at a break even.

Direct Questions

What strategies have you employed to manage costs in the wake of tightening gross margins?

Do you budget your expenses to a level your gross margin will cover, or do you try to achieve gross margin to cover existing expenses?

From the Home Quarter

One of these approaches is top-down, the other is bottom-up. If you caught my presentation at Sask Young Ag Entrepreneur’s Annual Conference earlier in January, then you’ll have already heard my explanation of why top-down is better.

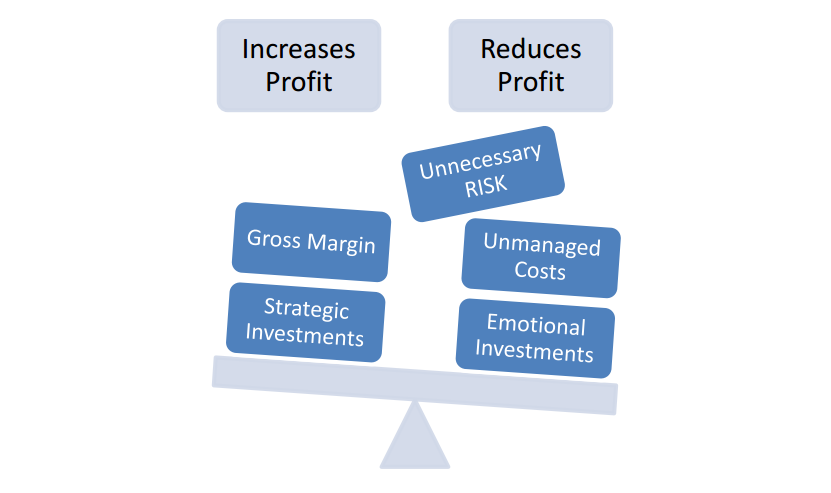

Top-down is managing your farm by budgeting your operating and fixed expenses to fall in line with your typical and expected gross margin. You have likely enjoyed a regular profit.

Bottom-up is reacting to a long line of expenses that were incurred during a short period of high profitability by trying to create a gross margin that is not very likely.

The view from the top is better.

Moe Russell has spent well over 30 years in farm finance

Moe Russell has spent well over 30 years in farm finance