Dichotomy

Here is a throwback to an article I wrote in August 2015 titled Is Data Management Really Important? where I highlighted a conversation between a friend and I that included his opinion that even large corporations let their “focus (be) primarily growth & profits and how to accomplish it, with information management being thrown together afterwards.”

While I believe that statement to still be true both for large corporations and farms alike, there is something in that statement that opens up what seems to have become the dichotomy of prairie grain farming: growth or status quo.

Let’s not get hung up on “growth’ as a single definition. In March 2015, my article Always Growing…Growing All Ways clearly described a few of the many ways we can achieve growth in our businesses that does not have to be pigeon-holed into the category of “expansion.”

So let’s clarify the dichotomy as “expansion or status quo.”

Now let’s compare a couple different scenarios.

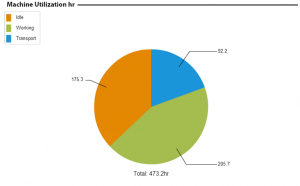

- In the spring of 2016, I met with a young farmer who started out in 2000 with nothing but an ag degree and desire. As he prepared to sow his seventeenth crop this spring, he showed me his numbers while admitting that he felt good about his financial position, but didn’t really know if he was good or not. He lost almost 20% of his acres from the previous year, and was happy about it because the cost to farm that land was too high and he knew it.

When I told him that I’d peg his operation in the top 10%, maybe even the top 5% of all grain farms on the prairies, he paused and said,”OK, so what are the top 5% doing that I’m not?” - There is a farmer who has been calling me off and on for a couple years now. By all accounts, it is quite a feat that he is still operating. Although he’s been farming for well over 20 years his debts are maxed out, leases are burning up cash flow faster than the Fort McMurray wildfire is burning up bush land. He spends more time running equipment that his hired men; he has no clue what his costs are; he has aggressively built his way up to 10,000ac and wants to get to 20,000ac; one of his advisors told me that his management capability was maxed out at 4,000ac.

The first scenario has the farmer focused on growth of profitability, control, and efficiency.

The second scenario has the farmer focused on growth of the number of acres on which he produces.

One would be the envy of 95% of farmers.

The other will never in his entire career get to the point of financial success that the first farmer has already achieved.

Direct Questions

Which are you more like, the first farmer above, or the second farmer?

Which farmer do you want to be like?

What are you prepared to do to get there?

From the Home Quarter

What has been described above is actually a false dichotomy. We’ve been led to believe that farms must get larger in order to survive and that small farms were doomed. What that message failed to deliver was “At what point is a farm large enough?” I am not decrying large farms or the continued expansion of farms…as long as it makes financial sense! The false dichotomy of expansion or status quo need not be black or white, left or right, mutually exclusive. Farms that are not expanding today could be expanding next year, just like farms that are expanding today may not be next year. Some farms that have expanded over the last few years might even be looking at reducing acres in the future.

Growth (expansion) at all costs can often come with the heaviest of all costs.